Let us try to understand this intrinsic property of fundamental particles.

Colour Charge is a property of particles like quarks and gluons, which are components of protons and neutrons (which in turn make up atomic nuclei).

This property is essential in the theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), which describes how these particles interact with each other.

Despite the name, colour charge has nothing to do with actual colours that we see. Instead, it’s a useful metaphor used by physicists to describe a type of charge, similar to how we use positive and negative to describe electric charge. In the case of colour charge, there are three types: red, green, and blue, as well as their corresponding “anticolors.” [note: 6 types of charge in pairs]

These “colours” come into play when quarks and gluons interact with each other.

—

Just like electric charges interact via electromagnetic force, colour charges interact via a strong force.

—

This interaction is mediated by gluons, the particles that carry the strong force.

—

Each gluon carries a colour and an anticolor, and they can change the colour charge of a quark when they interact with it.

The key thing about color charge is that it always balances out to be colour-neutral (or “white”) in observable particles. For example, a proton is made up of three quarks (each with a different colour charge), and their combined colour charges cancel out to white, making them neutral in terms of colour charge.

This balancing of colour charge is what keeps quarks bound together in protons and neutrons, and by extension, what holds the nuclei of atoms together. The force involved is incredibly strong, much stronger than the electromagnetic force that binds electrons to the nucleus, hence its name: the strong force.

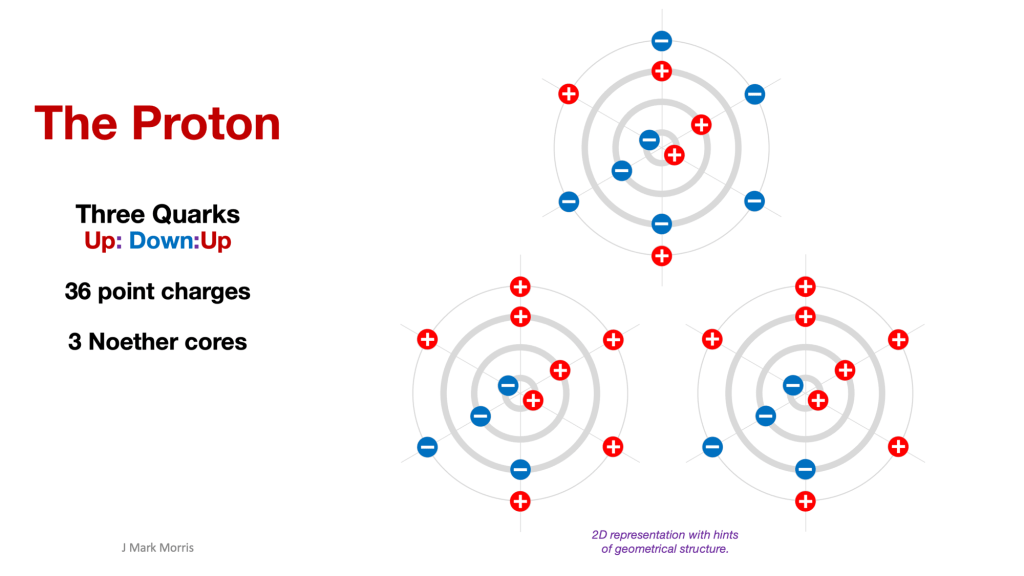

I found the following diagram and explanation helpful (from link):

Alright, let’s take this discussion and break it down and simplify this discussion on gluons, colour charge, and quarks within a proton.

- Basic Components: A proton is composed of three quarks: two up quarks and one down quark. These quarks are fundamental particles that help make up the nucleus of an atom.

- Quark Structure: The quarks in the proton are described as having a complex internal structure, represented in this discussion by a model called the “2-2-2-6 structure.” This includes something called a Noether core, which is a tri-binary (three-part) structure within each quark, possibly relating to how quarks generate their properties and interact.

- Orbits and Energy: Quarks have orbitals, which are paths or regions where you might find them acting like waves. These orbitals are at varying energy levels, with inner orbits being higher energy and smaller.

- Colour Charge and Gluons: Colour charge is a property exclusive to quarks and gluons (the particles mediating the strong force between quarks). Quarks come in three “colours”: red, green, and blue. In a proton, the three quarks must each have a different colour, leading to a balance where the combined colour is neutral (white). Gluons, which carry colour charge, can change the colour of quarks as they interact, maintaining this balance.

- Strong Interaction and Confinement: The strong force (mediated by gluons) is what binds quarks together inside protons and neutrons. This force is so strong that it confines quarks, meaning they can never be found alone; they always pair up or group in such a way that their colour charge balances to neutral.

Strong forces

The strong force, also known as the strong nuclear force, is one of the four fundamental forces in physics, the others being the gravitational force, the electromagnetic force, and the weak nuclear force. The strong force is primarily responsible for holding the nuclei of atoms together, and it operates at two levels: it binds quarks together to form particles like protons and neutrons, and it also holds these protons and neutrons together within the atomic nucleus.

Binding Quarks:

At the subatomic level, the strong force is responsible for binding quarks together through the exchange of particles known as gluons. Quarks are the fundamental constituents of particles such as protons and neutrons (collectively called baryons), and mesons. The theory that describes these interactions is called Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD). In QCD:

- Quarks carry a type of charge known as “colour charge,” which is analogous to electric charge in electromagnetism but comes in three types (often labelled as red, green, and blue).

- Gluons, which mediate the strong force, can carry a combination of colour and anticolour, making them able to bind quarks together by constantly exchanging these colour charges among the quarks, which effectively “glues” them together.

Holding Nuclei Together:

On a larger scale, the strong force also holds protons and neutrons together in the nucleus of an atom. This aspect of the strong force is often called the nuclear force or residual strong force. Despite protons having a positive electric charge and naturally repelling each other, the strong force overcomes this electromagnetic repulsion and keeps the nuclei stable. The residual strong force arises because the gluons and quarks within protons and neutrons also interact with those in neighbouring nucleons, maintaining a stable nuclear structure.

Characteristics:

- Range: The strong force is very powerful but has a very short range, acting only over distances of about (10^{-15}) metres.

- Binding Energy: It produces a very high amount of binding energy, which explains why such tremendous energy is released in nuclear reactions, including both fission and fusion.

- Colour Confinement: An interesting property of the strong force is colour confinement; quarks never exist freely by themselves but are always confined within larger particles.

Any attempt to separate quarks leads to the formation of new quarks and gluons

[no kidding? We will have to look at this more closely]

The strong force is essential for the existence of matter as it makes up the world, being the key force that binds the atomic nucleus together, allowing for the formation of atoms, molecules, and eventually, the structure of everything from stars to humans. [etc..etc..etc]

Binding Energy

Nuclear binding energy is essentially the glue that holds the nucleus of an atom together. It’s the energy needed to break a nucleus apart into its individual protons and neutrons. Here’s a simpler look at it:

- What is it? Nuclear binding energy is the amount of energy that would be required to split an atomic nucleus into its separate protons and neutrons.

- How do we understand it? Imagine you have a bunch of magnets stuck together; pulling them apart takes effort, or energy. Similarly, separating the protons and neutrons in a nucleus requires a certain amount of energy because they are tightly bound together by the strong force.

- Where does it come from? When protons and neutrons come together to form a nucleus, some of their mass is converted into energy (following Einstein’s famous formula (E=mc^2)), which then acts as the binding energy. This energy is like the heat and light you get when burning wood—the wood loses some mass in the form of ash, but you gain energy as heat.

- Why does it matter? The amount of binding energy tells us how stable a nucleus is. A higher binding energy means a more stable nucleus that’s less likely to break apart. For example, iron has one of the highest binding energies, which contributes to its great stability.

In summary, nuclear binding energy is the energy involved in either holding a nucleus together or the energy needed to break it apart, and it is a key indicator of the stability of atomic nuclei.

Any attempt to separate quarks leads to the formation of new quarks and gluons

The process by which new quarks appear when existing quarks are pulled apart is rooted in the principles of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), which governs the interactions involving quarks and gluons. Here’s a simple breakdown of where these new quarks come from:

Energy Conversion

In the quantum world, particularly under the rules of QCD, energy and matter are interchangeable, as described by Einstein’s famous equation (E=mc^2) (energy equals mass times the speed of light squared). This equation implies that under certain conditions, energy can be converted into particles, and vice versa.

The Process

When you attempt to pull quarks apart:

- Stretching the Gluon Field: Quarks are bound together by the strong force, mediated by gluons. These gluons form a sort of elastic “string” between quarks. As you try to separate quarks, you’re essentially stretching this gluon string.

- Increasing Energy: Stretching this gluon string requires a lot of energy. As the energy in the stretched string increases, it reaches a point where there is enough energy to create a pair (or pairs) of new particles.

- Particle Creation: The energy concentrated in the stretched gluon field can materialize into a new quark and its antimatter counterpart, an antiquark. This process is known as pair production. The original quarks and the newly created quark and antiquark recombine in such a way that they form new composite particles (like mesons or baryons), ensuring that no quarks ever exist in isolation.

Experimental Evidence and Theoretical Support

This behavior has been observed and studied in particle accelerators, where high-energy collisions result in the creation of many new particles. The theory and these experiments show that the energy used to pull quarks apart is directly converted into new quarks and antiquarks, following the conservation laws of energy and color charge (a type of charge in QCD).

This fascinating aspect of quantum field theory highlights how the fundamental forces and particles interact in ways that are counterintuitive compared to our everyday experiences, bridging concepts of energy, mass, and particle interactions in the universe.

Let’s look at this another way:

In a proton, the combination of quarks involves specific colours and flavours of quarks.

Here’s how the colours and combinations work within a proton:

Proton Composition

A proton is made up of three quarks:

- Two up quarks (each with a charge of +2/3)

- One down quark (with a charge of -1/3)

The sum of these charges gives the proton its overall charge of +1.

The Colour Charge

There are three types of colour charges for quarks: red, green, and blue. The colour naming is purely conventional and has nothing to do with actual colours; it’s just a way to describe the different states.

Colour Neutrality in a Proton

For a proton to be stable, it must be colour-neutral, meaning that the combination of colours within the proton must result in a colourless state. This is analogous to mixing red, green, and blue light to get white light in the visible spectrum. The quarks in a proton are thus arranged such that:

- One quark is red

- One quark is green

- One quark is blue

This configuration ensures that the proton is colour-neutral.

Role of Gluons

Gluons are the mediators of the strong force that binds quarks together. They are unique because they themselves carry colour charge. Each gluon carries a combination of a colour and an anticolour (e.g., red-antiblue, blue-antigreen, etc.). This dual colour nature allows gluons to change the colour of quarks as they are exchanged among them, ensuring the strong force continues to act uniformly and keeps the quarks bound tightly together.

Continuous Colour Exchange

The colours of the quarks inside a proton are not static. As gluons are exchanged between quarks, their colours change continuously, but the overall colour of the proton always sums up to neutral. For example, if a red quark emits a red-antigreen gluon, it becomes green, and the quark that absorbs this gluon would switch from green to red.

Let’s break down how a quark can change its colour through the emission and absorption of a gluon, using your example:

Understanding Color Charge and Gluons

In QCD, each quark carries a “colour charge,” and gluons, which mediate the strong force between quarks, carry a combination of colour and anti-colour. The colour used (red, green, blue) and their anticolors (antired, antigreen, antiblue) are just labels to describe the different types of charges and have no relation to actual visible colours.

The Process Explained

Suppose you have a quark that initially has a red color charge:

- Emission of a Gluon: This red quark can emit a gluon. Let’s say the gluon it emits is red-antigreen. The gluon carries away a red colour charge and an antigreen anticolor charge.

- Quark Color Change upon Gluon Emission: Since the gluon carries away red, the original colour of the quark, the quark must lose its red colour. To conserve colour charge, the quark’s colour changes to the anti-colour of the part of the gluon that was not emitted—green in this case. This is because emitting a red-antigreen gluon effectively changes the quark’s colour to green to balance out the loss of red (antigreen neutralizes with green).

- Absorption by Another Quark: Another quark, say a green one, then absorbs this red-antigreen gluon. When the green quark absorbs the gluon, it receives the red component from the gluon.

- Quark Colour Change upon Gluon Absorption: Since the green quark absorbs a gluon with a red colour charge, it must balance its existing green colour with the red it absorbs. The antigreen component of the gluon neutralizes the green, leaving the quark red.

Visualizing the Exchange

You can visualize this process as a colour swap facilitated by the gluon:

- The red quark emits a red-antigreen gluon and turns green.

- The green quark absorbs the red-antigreen gluon and turns red.

This continuous exchange of gluons and the consequent changes in color charges among quarks ensure that the strong force remains consistent and strong, effectively binding the quarks together in a stable structure like a proton or neutron. The conservation of Colour Charge and the need for overall colour neutrality in particles like protons and neutrons are fundamental aspects of QCD.

Energy and Binding

The constant exchange of gluons and the associated energy contribute to the binding energy of the proton, making it extremely stable.

In summary, a proton is composed of three quarks (two up and one down) each assigned a different colour charge (red, green, blue). Gluons facilitate the strong force by exchanging colours between quarks, ensuring that the proton remains colour-neutral and thus stable. This colour exchange is fundamental to the structure of all hadrons (like protons and neutrons) and is a key feature of the strong interaction as described by QCD.

It’s all fascinating. I hope we drilled down enough there. Please leave a comment if you found this, and others in the series helpful.

One more thing, as you made it this far i have included the following video, it starts slow but it helps understanding. Enjoy!

Leave a comment